Longevity Bloomington Newsletter #18 - The risk of NOT strength training

Plus nutrition myths not supported by science

Research Roundup - What is the risk of NOT strength training?

Strength training is often perceived by many as being dangerous. It is thought of as a task only for young athletes and something that is not suitable for adults 50+. Many well intentioned healthcare providers counsel their patients to avoid “heavy lifting” as a way to avoid injury. This misguided perception has led to only 12% of adults 50+ participating in strength training on a regular basis!

It is understandable why many people perceive lifting weights as dangerous. It does look more dangerous than other forms of exercise such as cycling, jogging or swimming. Ironically, research shows it is actually one of the safest forms of exercise in which you can participate. When done properly, research consistently shows that strength training reduces injury risk significantly. In this 2013 review of 25 studies, strength training was shown to reduce sports injuries by 70% and overuse injuries by 50%!

There is no activity that has zero risk of injury. You could get injured walking to the refrigerator, typing on your computer or walking up the steps. And, of course, many people develop aches and pain without having done anything at all! Structuring your life to avoid any risk of injury is futile. The better approach would be to weigh the risks against the benefits of a particular activity. In an attempt to minimize the (perceived) risk of getting injured, most people miss out on the massive benefits of strength training.

As you will see, apart from unfounded opinions and feelings, there’s nothing of substance to support the “lifting is dangerous” myth. Strength training is one of the most powerful tools we have at our disposal to improve quality of life as we age.

Is strength training safe for adults 50+?

If we are going to accurately assess the risks versus the benefits of strength training, we first must know the injury rate of participation. A review of 20 studies found the injury rate of strength sports like weightlifting, CrossFit and powerlifting to be approximately 2-4 per 1000 hours of participation. To put that number into perspective, if you spend 2-4 hours per week strength training, you could go 3-4 years without experiencing any injury whatsoever! Furthermore, the participants in this study were competing in the strength sports listed above. This means they were regularly lifting near maximal weight and the injury rate was still very low! The injury rate for an individual participating in strength training for general health purposes is likely even lower.

The researchers also noted that most of the injuries sustained in strength training tend to be minor aches and pains. The vast majority don’t require a visit to the doctor. A little bit of rest and some ice took care of most of the injuries.

What about the safety of strength training for adults 50+? A 2013 review on the effects of resistance training reported only one case of shoulder pain with lifting weights out of 20 studies and 2,544 subjects! The subjects in this study were considered “frail” and ranged in age from 70-92 years old! People of all ages can and should participate in strength straining and can do so safely.

What if you have diabetes, arthritis, high blood pressure, osteoporosis or almost any other chronic health condition? Is strength training still safe in these situations? Yes. You actually need strength training more than an individual without these conditions! As Jonathan Sullivan, MD says, “those conditions don’t prohibit (strength) training, they mandate it. All of these conditions suck. But they suck more if you’re weak.” Although unlikely, if you believe you have a condition that does prohibit your ability to participate in strength training, speak with your doctor.

“If you think lifting weights is dangerous, try being weak, being weak is dangerous.”

- Bret Contreras, PhD

What are the risks of NOT strength training?

When assessing the risks of strength training, most individuals only consider the injury risk. Most people do not think about the risks associated with not strength training. Unfortunately, if you do not participate in some type of strength training, the risk of getting weaker as you age is 100%. Muscle mass decreases approximately 3-8% per decade after the age of 30 with an even higher decline after 60. You can dramatically reduce this loss by lifting weights and making sure you are getting enough protein in your diet.

A loss of muscle mass is much more significant that most people realize. A reduction in muscle mass leads to a general decrease in physiological resilience. Physiological resilience is your ability to tolerate and recover from stressors. It is your ability to “bounce back” after a fall, hospitalization or surgery. Successful aging often depends on a person’s response to the inevitability of life stressors. Everyone is going to suffer an injury or illness at some point. Being physically fit is critical if you want to recover quickly and limit the consequences that injury or illness has on your health.

A large body of evidence links muscular weakness to a host of negative outcomes:

diabetes

disability

falls

cognitive decline

osteoporosis

early all cause mortality

Progressive resistance training in adults 50+ has consistently been shown to:

counteract muscle weakness and physical frailty

increase strength and muscle mass

improve physical performance

improve bone density

improve metabolic health and insulin sensitivity

improve management of chronic health conditions

improve quality of life

improve psychological well-being

extend independent living

reduce risk of falls and fractures

decrease abdominal and visceral fat

As you can see, the benefits of resistance training far outweigh the very small injury risk. If you do suffer an injury, most will be minor and will resolve on their own with a bit of rest and time. You are missing out on a potentially massive intervention to improve nearly every area of your life if you allow the misguided perception that “lifting is dangerous” prevent you from participating in strength training. Please consider the risks associated with NOT resistance training.

“Physical strength is the final interface between you and your environment. It’s the way you interact with your surroundings. It is the guarantor of your independence and the best insurance policy you can own for a satisfying existence.” - Mark Rippetoe

Nutrition Myths Not Supported by Science

Myth: carbs are unhealthy. You should avoid them when trying to lose weight.

For many years, fat was the enemy. In the 90s, low-fat diets were all the rage. Recently though, carbs have become the new scapegoat. Vilifying carbohydrates is quite popular these days. They are being blamed for everything from the obesity epidemic to the rise in diabetes.

A 2018 review of 32 controlled feeding studies compared low-carb to low-fat diets in terms of body fat loss. What did they find? Essentially, there was no difference between low-carb and low-fat diets. The differences between the groups were so small as to be “physiologically meaningless”.

Eating less carbs can be helpful if it helps you eat healthier or consume less calories. It can also be helpful to eat less carbs if it allows you to stick with your diet. BUT there is nothing inherently harmful about carbohydrates. If weight loss is your goal, the important part is to end most days on a caloric deficit.

Myth: fat is unhealthy. Fat makes you fat.

Similar to the carbohydrate argument above, dietary fat is not inherently bad for you either. Dietary fat is essential for many of our body’s functions. To reiterate, given the same caloric deficit and protein intake, low-carb and low-fat diets produce the same amount of weight loss. Trans fat is the only fat that has been shown consistently to be harmful. If you feel better on a high fat diet and this type of diet allows you to end most days in a caloric deficit, stick with it!

Myth: eating small meals throughout the day will boost your metabolism and will allow you to lose more weight

A 2007 study looked at the effect of meal frequency on weight loss. The researchers found no difference in fat loss between the group that had one meal per day versus the group that had three meals per day given the same amount of calories.

If eating small meals throughout the day makes you feel more full and allows you to resist the junk food in the pantry, go for it! On the other hand, if you have a hard time stopping eating once you get started, less meals may be a better idea.

Take home point: the frequency of your meals will have less of an effect on your ability to lose weight than the total daily caloric content of those meals.

Myth: low-fat or fat-free products are healthier choices

Many products labeled “low-fat” or “fat-free” contain added sugar and sodium to make up for the loss in flavor from removing the fat. If you are trying to reduce the amount of fat in your diet, look for naturally occurring low fat options such as lean protein, fruit and vegetables. Make sure to check the food label prior to purchasing processed “fat-free” products to make sure they don’t contain a surplus of added sugar and calories.

Myth: to lose fat, don’t eat before bed

While eating late at night can cause weight gain, it is not because there is anything inherently bad about eating at night. While there are a few studies showing a slight advantage to earlier eating, the cause of the weight gain is typically related to the increased caloric intake.

Oftentimes, people will eat at night for reasons other than hunger. These reasons include satisfying cravings or coping with boredom or stress. Snacks eaten late at night often consist of mindless consumption of high calorie processed foods that are easy to overeat. If you choose to snack before bed, try to choose options that are portion controlled to avoid taking in too many calories.

Longevity Members In Action

Yoga Pose of the Month

Yoga Pose of the Month: Standing Forward Fold (Uttanasana)

If your hamstrings are tight, this is the pose for you!

Standing Forward Fold lengthens the hamstrings, calves, and back. Practiced consistently over time, this pose can help you open the back of your legs and improve range of motion in the back.

Before we begin, remember that this pose is not about touching your toes. It is about lengthening the back of the legs and the back of the body mindfully and compassionately. No force, no tugging, no bouncing. We want to work from where we are.

Caution: If you have uncontrolled hypertension, glaucoma, or severe back pain, you may want to avoid this pose.

You may find it helpful to place a support (maybe a yoga block or two, a sturdy stack of books, or an ottoman) in front of your feet where your hands will be.

1. Begin by standing tall with your feet parallel to one another, about 6 inches apart.

2. Take a soft bend in your knees. Do not lock your knees.

3. Engage your abdominal muscles. Think about gently drawing the navel in and up toward the spine. A strong belly allows space for the back to open and can help avoid back strain.

4. Keep your spine long and hinge at the hip to fold forward. When you can hinge no farther, you can allow the spine to round.

5. Place you hands on your thighs, shins, or the support in front of you.

6. Let your head hang heavy. Think about the crown of the head pointing towards the floor.

7. Hold for 30-60 seconds, all the while breathing deeply.

8. Return to standing by first bending the knees deeply, bringing the hands to the hips, lengthening the spine forward, and hinging to stand with a flat back. This is the gentlest way to return to standing.

This video shows an option called ragdoll pose; you might try it, but standing forward fold is practiced in stillness with the hands supported on something.

If the body is tight or you are new to this posture, you can bend the knees even more deeply. You might even try bending the knees so much that the belly can rest on the thighs. A deep knee bend takes the stretch away from the hamstrings and allows you to focus on the back. With consistent practice, you are likely to find that once impossibly tight hamstrings begin to open and that you have more room in the back of your legs and your low back.

-Patricia Pauly

New Longevity Bloomington Members

We have added seven new members this month:

Susan

Larry

Beth

Marc

Maureen

Linda

Sandi

Welcome to the Longevity family. It has been great having you!

Longevity Bloomington Social Media

The squat is a great exercise to strengthen the muscles around your knee and hip. If you are having trouble performing a regular squat, here are some ways to modify the exercise. Start with whichever modification you can perform and go to the next exercise when it gets easy.

Aren’t squats bad for your knees? No! Squats are a great way to strengthen your thigh muscles. Improved strength in the muscles of your thigh has repeatedly been shown in the research to reduce pain from conditions such as arthritis.

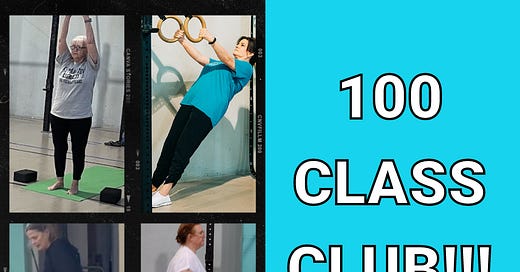

Please welcome Judy Childers, Kathryn Wright, Michelle Marcella and Stephanie Williamson to the 100 class club!!! Each of them have shown an incredible commitment to their health and fitness. We greatly appreciate each of you!